Designing For Euphoria

Discussing the concept of floors and ceilings in game design

Hello. First post. Welcome!

So thought I’d kick-off* with a post that is one part ‘getting to know me’ and one part setting out my stall. A long read about one aspect of designing games that I’ve been thinking about a lot recently when approaching my work.

As much as I love board games, I also have other hobbies, and I wanted to touch upon one of those this week - namely watching football (or soccer for you heathens across the pond). Specifically, I am a fan of Manchester United. My fandom extends beyond watching football to reading around the subject - revelling in post after post on subreddits, revelling in goals and wallowing in failures. I’ve loved football since I was wee, but there has been a notable turn in coverage in the last decade or so, most likely thanks to the social media machines that need constantly lubricated by content. They take matches and split them into a myriad chunks of shareable assets. More often than not they are statistics - often shared during or after a game, or else used in transfer windows to compare potential players based on their contributions across a game, seasons - and even careers. Things like “shots on target”, “passes completed” and in more recent years the futuristically labelled stat: “xG”.1

Stats themselves aren’t anything new. You know, when mid-match the commentator would notice a little graphic pop onto the screen and would say “Manchester United have had the lion’s share of possession in this half”, and a little single horizontal bar chart pops up where excel would have suggested a pie chart. I’ve always been fascinated by that kind of work, and you have to understand, this stuff was emerging in broadcast TV in the 80s and 90s, so it really was cutting edge stuff that I don’t think gets the credit it deserves. More recently, as I have been working as a graphic designer, I’ve begun to conceptualise what a fascinating job that must have been designing the early infographics to communicate quite boring information from the game to a very stats illiterate audience that might convey a sense of narrative - what can we learn from the stats of the game that have any baring on the viewing public?

But then when you look a little deeper - how did they know this? In my head, there were teams of people watching the match and noting when one team had the ball and the other team didn’t, and they’d press a little button. Maybe there was a chess clock involved. But then I’d think to myself, what if the ball is a few yards ahead of a player, is it still in possession of that team? How precise is this information? And they’d have to do this for all sorts of things - writing down a tally whenever someone made an attempt at goal, or noting when a pass was completed and when it wasn’t. One guy was on tackles, another on throw-ins. Like the oft hypothesized infinite monkeys, except a very finite number of low paid interns, on hand for dozens of matches at the weekend, and then presumably twiddling their thumbs all week waiting for more action.2

So now, in a post-moneyball world, maths terms have bled into the mainstream, and people discuss statistics like its nothing.3 Specifically, there is the concept of the floor and the ceiling, which if anyone has ever tried to model a dice throw in excel, may have used these to level out random numbers into integers. But for our purposes, a given team in football has a floor and a ceiling - the worst they can perform, and then their highest heights. Across a season, a team may perform within that imaginary range. To improve that team, however, one has a choice - do you bring in players that raise the ceiling? Find some method in training to raise the floor? Or do you lower either of these values to focus the team of consistency and aim to build from there?

So now, maybe 1000 words into this post, we turn to board games.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this concept of the floor and the ceiling in games, and I think it’s a healthy one when trying to get your own designs off the ground (pun intentional). Because, actually, a game’s floor, the lowest one can expect, is for a game to be a game - and this isn’t nearly as trivial a concept as you might think. There have been many occasions when I’ve thrown everything for a week or two into a prototype, printed out decks of cards, labelled up components even crafted game boards - only to discover the game simply does not work.

I’m not even talking games which are not fun to play, I mean literal unplayable garbage. And yes, please subscribe to my newsletter and one day buy my games - what a brag! The games I produce may not even work! What a brave marketing pitch!

There are games which don’t function properly, the bits aren’t connected coherently or the systems don’t interact enough. But then there is the other end of things - when you work your bottom off to get a game prototype that works, the cogs of the game come together and yes I could put that on someones table and hand on heart claim that by the dictionary definition of a game, it is a game. It plays. It has a coherent floor, a stage onto which our players can dance. But the ceiling on that game, is terribly low. Stiflingly low.

What we mean by this is that it isn’t fun, or it hasn’t got the space for you to even find fun somehow playing it. You can reach a conclusion, find yourself a winner and still not be much satisfied by the experience. I know firsthand that there are games that go to market with this in place, and often by design. I’m thinking here of the seasonal aisles in supermarkets which every so often find themselves brimming with increasingly good looking low effort dinner party games - safe, narrow gaming is cheaper, a more consistent experience to hone, and much less likely to lead to disagreements.

Raising the ceiling of a game means providing the space for players to find for themselves a means to win; strategy, narrative and choices that give the player scope to immerse themselves in the game. It means less hand holding, taking away the stabilisers for how a game plays out or how a player is expected to behave - but these lead to moments of joy that escape the confines of the game four walls.

For a rather substantial article on the subject, I don’t mean to dwell on the precise understanding of this ceiling and what it means in its practicalities, merely touch upon the concept as I seek to explore this idea in my game designs and future posts around moments in board games that elevate beyond the table. But importantly I want to emphasise this: it isn’t necessarily a strict gameplay mechanism that peaks at a moment in the game, or even in the winning of a game that the joy is found, but a potential that enables players to have and enjoy an emotionally heightened moment for themselves.

Of course, a game with a low floor and a high ceiling may not itself be desirable; there are plenty of configurations one can imagine, it depends on your design ethos and intended participants. But I think this is a nice concept to introduce early doors within these pages.

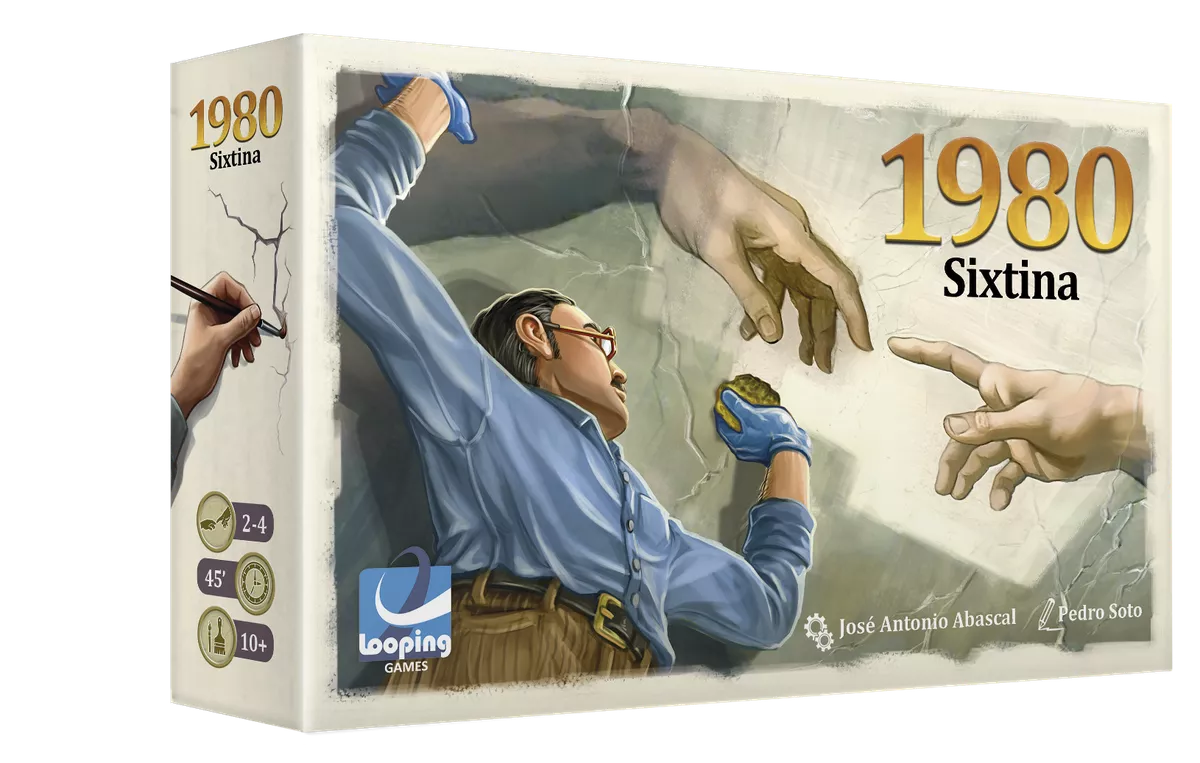

Lo and behold, a cursory glance at Board Game Geek presents us with an actual game (1980 Sixtina) about restoring the ceiling of the Sistine chapel, there really are so few rocks left unturned.

Which brings me back to football. It is a game after all. It was not designed, per say, but it was brought about through years of evolving rules. It has one of the lowest floors you can imagine - kicking something round is an act so primitive you could imagine it played by gorillas. And yet, football is enjoyed throughout the world - with support estimated to be in the billions. Why each of us enjoy the game can be built around the narrative of their team, or more recently, the players they may support. But one can enjoy the game as a neutral; great success is one thing, but a great goal shows great skill and execution, and is often built around beautiful tactical interplay by the whole team that can be appreciated despite a particular affiliation. Tie these elements together, and you can begin to understand why football has such broad appeal.

In 1999 Manchester United were on the cusp of an incredible sporting achievement. The treble had never been achieved in British football - to do so would require three significant things: to dominate the top flight league week in week out, navigate a tricky FA cup against one of teams out for glory and then also to flourish in Europe, a competition won by a British team maybe once a decade, if that. For the opportunity to arise is one thing - to achieve it, next to impossible.

United, with a team built around their academy that had been growing year on year into consistent champions - had it in their sights. League won, an FA Cup lifted - and a final booked in Barcelona. But for their final game, two of their most important players couldn’t be involved because of suspensions - having both given their all in the semi-final, sacrificed themselves without question for their team.

Then came the match. They played terribly, going 1-0 down to a very strong Bayern Munich side, another giant in European football. In a last throw of the dice, Sir Alex throws on some subs that unbalance the team, but show intent - to chase the match. Now usually, when the result of that match matters, and there is next to no time left, a goalie might come up for a corner - the extra man means all the defenders are occupied, plus the frame of a goalkeeper, often tall and large, becomes an excellent target man for a header and an unlikely game winner. Of course, if the corner is defended, this leaves a full pitch of space for the defence to knick a goal - so seeing the goalie coming up for a corner is a dramatic rarity, just common enough to be a trope of a side throwing everything and the kitchen sink at the game.

Seeing United’s keeper come up for a corner in the dying embers of the game meant there wasn’t much left that the team could give - we were in last chance saloon. But a corner had been won, and with a corner there was always a chance. For united, the keeper wasn’t found but… a goal was scored. Teddy Sherringham, one of the subs, found the net in dramatic fashion. In this act, the match had been turned on its head - and the game would be taken to extra time. 30 minutes potentially, in which a now depleted and unbalanced side would have to survive, but it was a glimmer of light in a terrible evening.

But before the referee could call the 90 minutes to a close, United get another corner. With the pressure of losing subsiding, the team on the ascendance, the ball is played into the box. The other sub, a fella by the name of Ole Gunnar Solksjær - the baby faced assassin - sticks out a leg and puts the ball into the back of the net. I still get goosebumps thinking about this moment. In the last scraps of the match, my team had turned around certain defeat into the dream Fergie time result, not only winning the match, not only winning the cup, but claiming for the first time in British history - a treble. You very rarely get to experience these historic moments and know that you are watching history - and it not be a terrible tragedy. This was a moment that will forever stick with me - and it was nothing but a game.

It’s as close to the highest ceiling of a game I could imagine. It has everything - narrative, tension, chaos, achievement and risk. If you could encapsulate that feeling, bottle it up and sell it, you’d be a millionaire tomorrow. Were you to ever design a game with the capacity to reach those giddy heights with any degree of regularity, that my friend would be a game worth playing.

So what is in your game? What could possibly happen with the scraps of card and dice that could ever make a player sing? Let me know in the comments of any games you’ve played that have inspired something magical - good or bad - and I’ll be following up some of these in guest posts over the next few weeks - the highs and lows of gaming!

Also known as ‘expected Goals’. It is a measurement of potential goal scoring opportunities that make a rash statistical analysis of every single moment in a goal in which the ball is played towards the opposing goal. How likely this shot-like-action results in a goal bing scored is then displayed between 0 and 1 - 1 being certain. A penalty has an xG, depending on the model used, of at least 0.5 and often as high as 0.8 - the chance of a goal not being scored from a penaly therefore is about 1 or 2 in every 10. All these chances are then collated together to give the team an xG for that match - meaning that from all the chances you could suggest a goal being scored x amounts of the time. Honestly it’s such an exciting and controversial part of the modern game.

These days of course, you can use AI to watch games and parse that information for you, creating heat maps of player movements for example, and I even watched a youtuber explain how to do all this for yourself using Python. We really are living in the future where not only can so much be achieved by yourself for little investment, but other people go out of their way to make tutorials for all these complex things, spoon feeding you complex computer generated computer analysis, and for free!

Moneyballing I suppose would be the concept of understanding a player based on their underlying numbers. From the book, and then film starring Brad Pitt, of the real life Oakland A's baseball championship winning side which turned conventional scouting on its head as they found incredible value in discarded players who were displaying some otherwise hidden ability that could only be found by looking at their stats. All sports have attempted to replicate this, because fundamentally the magic trick is an economic one - building a successful squad by spending less money - but not all sports can translate these metrics to on the field success for whatever reason.